Introduction

If there is life in our solar system beyond Earth, it is likely to be hiding in the subsurface of Mars or on icy moons like Europa and Enceladus. Our lab likes to investigate life in challenging environments on Earth in order to develop best practices for attempting to detect life elsewhere. For example, we have been exploring subseafloor life of the Atlantis Massif, a giant submarine mountain in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

We recently completed a big project at this site, which is described in our lab’s latest publication, “Microbial Residents of the Atlantis Massif’s Shallow Serpentinite Subsurface”. The lead author is Sheri Motamedi, and this paper is from Sheri’s Ph.D. dissertation, which she successfully defended in May 2020. In this study, Sheri sequenced DNA from subseafloor rocks collected during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 357: “Serpentinization and Life”. In this essay, I want to describe the huge amount of work that went into collecting, processing, sharing, and investigating these samples by a whole team of international scientists, including Sheri’s heroic efforts to disentangle bona fide subseafloor DNA sequences from potential contaminants.

One theme of this story is that the issue of contamination of life detection experiments is a multi-faceted, interdisciplinary problem that is fundamental to microbial ecology and astrobiology.

IODP Expedition 357: “Serpentinization and Life”

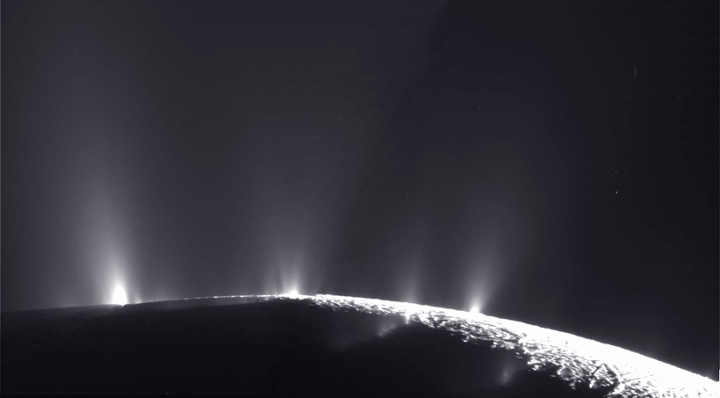

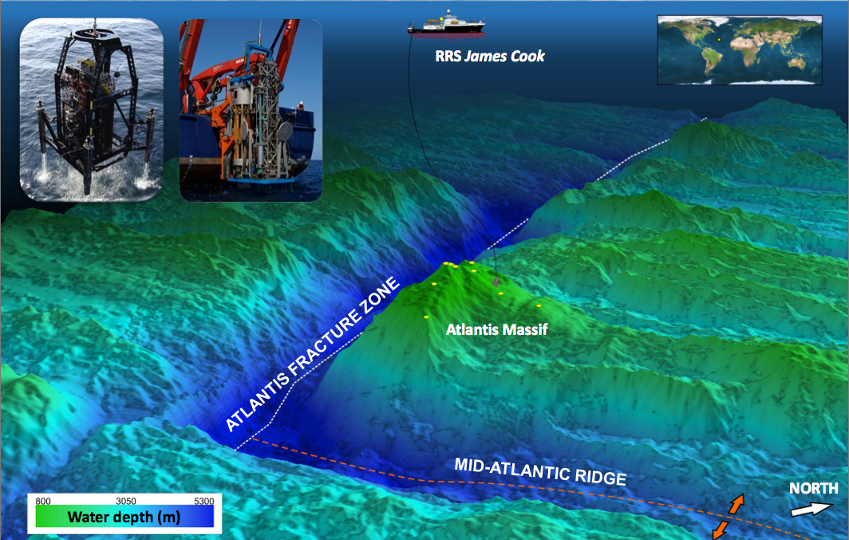

In October 2015, an international team of scientists and engineers embarked on a 47-day expedition aboard the RRS James Cook to investigate subseafloor life in the chain of submarine mountains in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This expedition targeted one mountain, in particular, named the Atlantis Massif, because it is primarily composed of one special kind of rock called “serpentinite”. Serpentinites are formed when rocks from the Earth’s mantle are uplifted and exposed to water and thereby “serpentinized”, a geochemical process that releases hydrogen gas (H2) and is thought to have played a role in the origin of life. The process of serpentinization fuels a whole ecosystem of diverse microbes in the huge chimneys of the Lost City hydrothermal field, and it may be responsible for the ongoing geysers emanating from Enceladus. A major goal of this expedition was to investigate the relationship between serpentinization and life so that we can better understand the origin and early evolution of life on Earth and to inform the search for life on other worlds where serpentinization is expected to occur.

In order to search for life inside these serpentinite rocks, we had to drill into the seafloor. Typically, ocean drilling (either for scientific research or for oil exploration) is conducted in seabed sediments, which are basically compacted mud. In some parts of the ocean, these sediments can accumulate into columns thousands of kilometers thick, which are scientifically and economically valuable for many reasons. It is very rare for ocean drilling expeditions to drill into the bedrock underneath the sediments because 1) there are currently no profitable resources to be extracted from the bedrock (but that may change in the near future) and 2) drilling into hard rock on the seafloor is extremely challenging from an engineering perspective.

In order to drill into and core the bedrock serpentinites of the Atlantis Massif, IODP Expedition 357 utilized two seabed drills, adapted for drilling into hard rocks for the first time. They were the Meeresboden-Bohrgerät 70 (MeBo) rock drill from the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM; University of Bremen, Germany) and the RockDrill2 (RD2) from the British Geological Survey (BGS). The adaptation of these drills and the many associated technical innovations represented a major engineering accomplishment of the expedition. You can read more about these accomplishments and other outcomes from the expedition in the Expedition Report and the associated publication, led by Chief Scientists Gretchen Früh-Green and Beth Orcutt.

Sampling subseafloor rocks for microbiology

Not surprisingly, the expedition encountered some technical difficulties when drilling into seafloor bedrock with new technology, but after 47 days of persistent engineering troubleshooting, the team obtained rocks from 17 boreholes totaling 57 meters of cores, each core ranging from 1.3 to 16.4 meters below the seafloor. When the rocks reached the ship, they were processed according to a highly complex procedure that the scientific team worked out over many, many conference calls and emails during the years of preparation for the expedition. The recovered rock cores had to be sectioned and subsampled for a countless number of analyses to be performed by the 34 members of the scientific team, each of whom contributed unique skills and techniques. These subsampling procedures had to be compatible with and customized for a range of specialized analyses from many disciplines including structural geology, petrology, geochemistry, paleomagnetism, organic chemistry, fluid chemistry, microbiology, and genomics. In addition, preserving a cohesive sequence of the core has immense geological value on its own, so all of the sectioning and subsampling of the rock cores had to be conducted in a manner that did not destroy the overall integrity of the core sequence.

Microbiology was an unusually prominent component of this IODP expedition because of the potentially profound links between serpentinization and life. Conducting microbiology experiments with seafloor rocks entails another set of technical challenges on top of the basic engineering challenges of obtaining the rock cores in the first place. A common theme of these challenges is the importance of minimizing and detecting contamination. During the recovery and handling of the rock cores, the scientific team employed at least six different contamination mitigation strategies:

-

A synthetic tracer (PFC: perfluoromethylcyclohexane) was injected into the drilling fluids during coring. Any rock cores with detectable levels of this tracer can be considered to be contaminated with seawater during drilling. The successful development of this tracing system was an engineering accomplishment of its own. See this paper by Orcutt et al. for more information.

-

The surfaces of approximately half of the rock core subsamples intended for microbiological analyses were flame-sterilized with a butane torch aboard the ship. Any organic matter on the surface of these rock samples would be charred, destroying any DNA.

Nan Ming of the Kochi Core Center shaving the exterior surfaces of a subseafloor rock core. Photo credit: W.J. Brazelton. -

The surfaces of intact core sections were shaved with a microbiologically clean rock saw inside a clean room facility dedicated to the purpose at the Kochi Core Center in Japan. Presumably, subsequent analyses of these samples would only include materials from within the rock that had never previously seen the surface of the Earth.

-

Many of the rock samples were quite rubbly due to the extensive alteration that occurs during serpentinization (and also during drilling and recovery) and were not amenable to shaving with a rock saw. Therefore, instead of shaving, these samples were rinsed with sterile, ultrapure water in an effort to remove surface contamination from the rocks, leaving only materials protected from the exterior environment. This rinsing procedure was also conducted in the clean room at the Kochi Core Center.

-

During the expedition, many samples of seawater were collected as potential sources of environmental contamination. These seawater samples included samples collected with bottles attached to the rock drills themselves, deep seawater samples collected during CTD rosette casts, and with a simple bucket deployed over the side of the ship to collect surface seawater that frequently crashes onto the deck of the ship. This extensive water sampling was led by postdoctoral researcher Katrina Twing (who is now an Assistant Professor at Weber State University).

-

Katrina also collected samples of various lubricants and other petroleum-based products used on the ship and the rock drills as additional potential sources of contamination into the rocks. We are currently preparing a manuscript reporting these results, led by undergraduate alum Lizethe Pendleton. The ubiquity of petroleum-based products is also a menace to the organic chemistry component of this expedition, as Susan Lang’s lab explored in this paper.

Purifying DNA out of a rock

All of the procedures above were conducted aboard the ship and at the Kochi Core Center before the samples were sent to our lab in Utah, where Sheri was able to begin working on them. Sheri had been preparing for this moment by developing a new DNA extraction and purification protocol. Before we collected the samples, we already knew this would be an extremely challenging project. Even though we are interested in serpentinites because of their potential to support biological activity, we were expecting the overall biomass per gram of rock to be very low. In addition, the minerals found in serpentinites are very potent inhibitors of sequencing reactions and are also very good at binding DNA (one of the reasons why they might have played an important role during the origin of life!). There are many commercial products for purification of impurities from DNA preparations, but these products are typically optimized for high-biomass materials like soil or fecal samples. As far as I know, our new protocol is the only method optimized for ultralow biomass and high mineral content.

Sheri’s final protocol (published in the supplement to our new paper and available in this github repo) employs multiple strategies to address these challenging samples:

-

We make all of our own reagents so that we can control their cleanliness and purity (i.e. no commercial kits). Obviously, we have to purchase some individual ingredients, but then we can assess contamination levels in each ingredient separately, making contamination events much easier to investigate.

-

The protocol includes the addition of sodium pyrophosphate and ATP to saturate all DNA-binding sites of the minerals prior to cell lysis.

-

Physical lysis of cells was accomplished with a bead beater, but no glass beads were added because they represent a significant source of contamination and because our tests indicated that the crushed rock minerals themselves provided sufficient material for smashing cells during beating.

-

The crude lysate was washed with warm TE buffer and ultrapure water in Vivacon2 filtration units (100,000 MWCO, ETO-treated) to remove low-molecular weight, soluble impurities and to reduce the conductivity of the solution to an acceptable level for the Aurora purification system (next step).

-

The washed lysates were purified with the Aurora purification system from Boreal Genomics. This is an electrophoretic system that purifies DNA from proteins, humic acids, and other impurities. A major advantage of this system for our project is that we can concentrate and purify DNA from a large volume of washed lysate down to a small final prep of only 40 - 70 uL. This is very convenient for extracting DNA from ~40 grams of rock at a time. This final prep from the Aurora system is extremely clean and suitable for PCR and sequencing.

Note that the protocol does not include any phenol extractions or ethanol precipitations, which we avoided because they inevitably result in significant loss of DNA. We did not perform controlled comparisons, though, so we don’t have proof that the yield of our new protocol is better than previous methods. The fundamental reason for this is that the final, purified DNA was still below the detection limit, so our only metric of purification success was our ability to obtain DNA sequences.

Also, this protocol is definitely not high-throughput. Sheri spent >3 days on each sample, working 11 hours per day. Processing 35 rock samples through this protocol was many months of work, and that was after the years of developing and optimizing the protocol.

Contamination control in the lab

In addition to all of the contamination mitigation procedures conducted on the ship and at the Kochi Core Center, we followed rigorous contamination control measures in our lab at Utah. We converted a supply closet into a dedicated clean room with a filtered air supply and a digital dust monitor. Sheri did not handle any samples when the lab experienced elevated dust levels. In addition, all samples were handled inside a PCR hood that was thoroughly cleaned and UV-sterilized between samples. Sheri also extracted and sequenced DNA collected on 0.1 um filters through which we pumped ambient lab air. These acted as our “extraction blanks”, but more specifically represented potential contaminant sequences from our lab air. Sheri also extracted DNA from extraction blanks, in which she added ultrapure water to the extraction buffer instead of rock samples, but these extractions contained essentially zero DNA, even before purification, thanks to our extremely careful lab procedures.

Identifying contaminant DNA sequences with bioinformatics

We submitted our final DNA preps for Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene at the Michigan State University genomics core facility, where the staff have been very willing to try their best to obtain high-quality sequences from our tiny quantities of DNA. We obtained a total of >1 million read pairs from the rock samples, including >2,780 read pairs from each of our 15 serpentinite samples and >10,000 read pairs from 5 of the serpentinites. We considered these results to be encouraging, considering that each of the final, purified preps contained less than 0.5 ng of DNA per uL. In addition, we obtained >27 million read pairs from the seawater and filtered lab air samples.

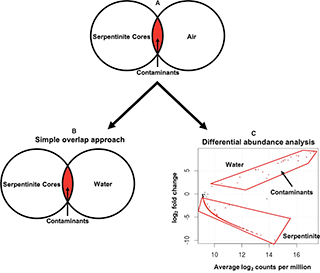

Despite the many contamination mitigation procedures described above, we could not assume that the DNA sequences obtained from the rock samples were completely free of contaminants. Therefore, the next technical challenge of this project was to distinguish DNA sequences representing true, subsurface organisms from those representing contaminants. Traditionally, identifying contaminants in sequence data has been accomplished with what we call the “simple overlap” approach, which can be conceptualized as a Venn diagram comparing the total DNA sequences from the samples of interest and the total DNA sequences from control samples (see Figure 4 in Motamedi et al. 2020). Any sequences found in both the samples of interest and the controls (the Venn overlap) are considered to be contaminants, and there are many examples in the literature of researchers simply deleting such sequences from their datasets.

We are uncomfortable with the simple overlap approach because of its implicit assumption that all contamination occurs in only one direction: from contamination sources into the samples of interest. However, in many cases, it is also likely for biological materials to be transported from samples of interest into control samples. For example, a tiny droplet of DNA from a high-biomass sample could fall into a well or an open tube representing an extraction blank, which contains essentially zero DNA. This would be identified as a contaminant during data analysis, resulting in the removal of the most abundant “true” species from the sample of interest. As our DNA sequencing methods become more and more sensitive, this problem of highly abundant sequences “reverse-contaminating” our blanks and controls will become more and more prevalent. (We are now using a nice tool called decontam to evaluate these specific scenarios, although we were unable to use it for Sheri’s paper due to our extremely low concentrations of DNA.)

Another limitation of the simple overlap approach is that it is not relevant to scenarios of environmental contamination where multiple sample types are expected to mix with each other in nature. This type of environmental contamination was the primary concern during recovery of the Expedition 357 rock cores because it was impossible to prevent the rock cores from being exposed to seawater. (They were sitting underneath the ocean!) Again, despite the many layers of contamination control measures described above, we could not assume that the final DNA sequences did not include any contaminants, especially because seawater contains a much higher density of microbes than found in the rocks. Furthermore, we could not assume that contamination between seawater and rocks occurs in only one direction because the Atlantis Massif is hydrothermally active (with the Lost City chimneys as one particularly dramatic example), and cameras on the rock drills recorded fluid flowing from the boreholes (Figure 13 of Fruh-Green et al. 2018). This hydrothermal flow may transport subsurface microbes into the overlying seawater, where they could be detected as “seawater” organisms.

Differential abundance analysis

To disentangle the mixing of seawater and rocks, Sheri adapted a technique from gene expression studies known as “differential abundance”. The relative abundance of each individual sequence is compared among all seawater and rock samples. Those sequences that are significantly more abundant in the seawater samples but also detected at least once in the rock samples are considered to be contaminants. We interpret these sequences as being much more likely to have originated in seawater, where they are more abundant, and contaminated the rock samples. Conversely, sequences that are much more abundant in the rock samples but also detected at least once in the seawater samples are considered to be true rock inhabitants. Their presence in seawater can be explained by hydrothermal circulation or laboratory contamination. (Sheri explored the possibility of hydrothermal circulation in another chapter of her dissertation which is not yet published). Note that the simple overlap approach would have labeled these sequences as contaminants and removed them from the dataset, even though they may be the most exciting results from the project!

In her paper, Sheri highlighted 20 different DNA sequences that were eliminated by the simple overlap approach but not by the differential abundance approach (all results available in our github repo). Initially, we were surprised that this number was so low, but we think it is due to the extraordinary efforts to minimize and remove seawater contamination during handling of the samples aboard the ship and in the Kochi Core Center. Projects without such extensive procedures are likely to result in much more stark differences between the simple overlap and differential abundance approaches.

Taxonomic identification of contaminants

In addition to identifying contaminants based on their relative abundances in our samples of rocks, seawater, and lab air, we evaluated the likelihood that each DNA sequence was a contaminant based on its taxonomic classification. Taxonomy-based identification of contaminants is extremely common and even integrated into the automated pipeline of some DNA sequencing facilities. The rationale is that some taxa (e.g. Burkholderia, Ralstonia, Sphingomonas) are frequently detected in blanks and control samples and should be treated with suspicion. In Sheri’s paper, we handled such cases by flagging them as suspicious in our published data sets (e.g. Data Set S7 of our paper).

You will still find these suspected contaminants in our published raw data because permanently deleting them seems unwise for a number of reasons. One is that taxonomic classification is constantly subject to revision; updates to software or databases can substantially alter the taxonomic assignment of a sequence. Secondly, the term “contaminant” does not reflect an ecological niche or a particular evolutionary history. It is only meaningful within an experimental context, and the same taxonomic group could be a contaminant in one context and the most important group of interest in another context.

This point is especially pertinent to extreme environments that have never been previously studied. Organisms that are capable of persisting in the extreme environments of mostly sterile laboratory supplies may also be capable of inhabiting nutrient-poor, extreme environments. In Sheri’s paper, we highlighted one example sequence classified as Acidovorax, a bacterial genus that is found in soil, plants, and laboratory reagents. Its ability to form biofilms in a wide variety of environments could also increase its fitness in the basement rocks of the Atlantis Massif. It was not detected in any of our potential contamination sources. Therefore, we included this sequence in our final list of potential subsurface bacteria but highlighted it as a potential contaminant, based on previous studies.

The stigma of contaminated datasets

Even though there is widespread agreement that contamination detection is an important, unsolved technical challenge for environmental microbiology, the stigma of publishing a “contaminated” dataset remains a constant threat, especially to early career scientists. It is common to hear complaints that there are “contaminated” datasets in the public databases, as if there is any such thing as a non-contaminated dataset. As a community, we should move beyond the simplistic binary of studies being either contaminated or not contaminated, as if some impossible standard of purity is the main goal of our science. Instead, we should frame our discussions around sampling design and the rationale behind data analysis strategies, in recognition that all datasets are contaminated and that the scientific value lies in our interpretations of those datasets.

The dichotomy of “contaminated” vs. “clean” datasets is a consequence of microbiologists treating environmental sequencing datasets as the final product of their work and as direct representations of truth. We often behave as if our DNA sequences will plainly reveal nature, if only we can implement sufficiently sterile techniques. Instead of simply documenting nature, we should reconceptualize environmental DNA sequencing studies as experimental results, with the main focus re-centered on the scientific value of our interpretations of those results in the context of experimental and natural conditions. This view of DNA sequences as experimental tools might stimulate efforts to develop creative sampling designs and clever data analysis strategies that should be more fruitful than a single-minded obsession with producing “clean” raw data. Sequencing data do not represent reality. They are experimental results with which we can construct models of reality.

Our lab has taken one small, mundane step in this direction by publishing all of our processed data and interpretations (as a supplement to the paper and in our github repo) in addition to the raw sequence data submitted to the NCBI SRA public repository. The raw data contains many contaminants, and we have attempted to show exactly which sequences were identified as contaminants (and how we did so) and which sequences we currently think represent true subsurface microbes. We expect to revise those interpretations over time, in collaboration with others in the community, because that’s how science works.

We are not alone in these efforts. Here are additional examples of studies that have attempted to wrestle with these difficult issues.

Next steps and future directions

Throughout this project, from initial planning meetings to final data analyses, we were continually confronted with the multi-faceted and multidisciplinary layers of difficulties inherent to managing contamination in a big environmental microbiology project. A major lesson from this project is that there are many different kinds of contamination, and addressing them all requires multiple strategies, including careful laboratory work, detail-oriented project management, and thoughtful data analysis. We are proud of our recent paper because we did our very best to address as many of these issues as we could, but certainly not because we think our specific techniques are the very best possible. This is a young field with a vibrant community, and we’re only getting started.

Two important areas for improvement are 1) to use more quantitative measures of environmental abundance and 2) to incorporate physical models of environmental dispersal. In our study, cell numbers and DNA quantities were so low in our ultralow-biomass rocks that no sample-specific quantitative estimates of natural abundance were possible. In our future work, however, our goal is to include these abundances in our evaluations of contamination sources, using the basic logic that contamination is most likely to occur from areas of higher abundance to areas of lower abundance. This goal is synergistic with our second goal, which is to integrate these contamination analyses with physical models of dispersal. The basic idea here is that if we know how water or air is moving through an environment, we can design sampling strategies to test specific scenarios of environmental contamination. We already do this in simplistic, intuitive ways, and we can expand these into more explicit experimental designs.

Contamination is a special case of dispersal, and dispersal is fundamental to astrobiology

Once we think about contamination as something that happens naturally in the environment as well as in the lab and also as something that can be modeled as a consequence of physical dispersal, it becomes clear that environmental contamination is a special case of dispersal, conceived in a particular experimental context. Contaminant cells are simply microbes who are dispersing into our sample containers. (Laboratory contamination is often dispersal of DNA molecules, which may or may not be as ecologically relevant.) In this context, one can conceptualize the goal of contamination detection as the experimental determination of a cell’s true environmental habitat.

These contamination issues are fundamentally the same whether one is attempting to detect life in subseafloor rocks or in the ocean of an icy moon of Jupiter. Controlling and detecting contamination is a critical technical challenge with these experiments, but the concept of “contamination” is also the fundamental epistemological challenge of astrobiology. When we distinguish between “contaminants” and “aliens” in an astrobiology experiment, we will be attempting to experimentally determine the path that a cell or a molecular sequence followed on its way to dispersing into our sample collection container.

Two examples to further illustrate this point:

-

Consider Sheri’s DNA sequences that were more abundant in subseafloor serpentinites but also detected in seawater. Were they transported from the rock samples into the seawater for the first and only time last year during DNA extractions in our lab? Or were they transported into seawater many years ago during hydrothermal circulation and floated in the ocean until we sampled it? Or were they flushed from the rocks into the surrounding seawater during drilling? Or have we observed an equilibrium abundance ratio that was reached only after millions of years of seawater circulating throughout the oceanic crust? We currently lack the methods to distinguish these scenarios.

-

If we detect DNA in the plume of Enceladus, we will have to ask whether the DNA arrived there only minutes earlier as contamination from the spacecraft. Or maybe it arrived there years earlier as contamination from a previous mission that was not subjected to stringent sterilization protocols? Or was it transported to Enceladus billions of years ago by a meteorite as “contamination” from another planet? Or by a comet as “contamination” from the outer solar system? These are very different scenarios with very different scientific implications, and it’s not clear that we already have the data analysis tools that would enable us to distinguish them.

In summary, contamination is a special case of dispersal, and extraterrestrial life detection experiments are implicitly testing dispersal. Therefore, progress in this area can be achieved by experimental investigations of microbial dispersal in a variety of environmental settings.

Acknowledgements

This was just one of many ongoing projects conducted by the international team of scientists participating in IODP Expedition 357, led by Chief Scientists Gretchen Früh-Green and Beth Orcutt. This essay benefited from many discussions with the science team and from proof-reading by Beth Orcutt and Susan Lang. We are also grateful to the Kochi Core Center for their assistance and for use of their facility. Several past and current members of our lab contributed to this project. Sheri Motamedi led the project, as detailed above. Katrina Twing coordinated the collection of potential contamination sources aboard the ship, including a comprehensive survey of surrounding seawater. Lizethe Pendleton extracted and sequenced DNA from all of the water and grease samples. Christopher Thornton contributed ideas and computational tools for tracking contaminant DNA sequences. Alex Hyer, Emily Dart, and Julia McGonigle provided laboratory and computational assistance. Financial support was provided by the NASA Astrobiology Institute Rock-Powered Life team and the U.S. National Science Foundation-funded US Science Support Program.